GENIUS LOCI

SENSE OF PLACE

“Hobart belongs to Mount Wellington.”

William Charles Piguenit, A Mountain Top, Tasmania

TMAG

In thy prostrate columns, lichen-clothed,

I saw the wreck of temples Titan-reared.

S. H. Wintle, Ode to Mount Wellington 1868

The human body is composed, 98%, of water. For Hobartians, whose water comes from the mountain, all have the mountain in them. For a few, it would make up the bulk of their bodyweight. The mountain is in the air they breathe. Its aromas are lodged in their memory. To those who scale its slopes, the mountain is embedded in the palms of their hands and the skin of their shins.

It is engraved in memory as well as ingrained in the body. Shut your eyes, Hobartians, and ask yourself Where is the mountain? Even if your geographic intuition was off, the mountain exists in your mind.

You cannot take the mountain out of Hobartians.

“Place is not a given fact, but the sum of the relationships, social and ecological, that exist in a certain area. It is a process, an ongoing movement through both the past and the future, and it is never a fixed topographical area. It is ... the way we feel and have felt about our home.”

Adam Barns in his thesis Mount Wellington and Sense of Place quotes Relph and applies him: ‘The mountain stands over Hobart drawing the earth to the sky. It is an intrinsic element in the genius loci of Hobart and its surrounds. As people experience the genius loci their sense of place embodies a particular relationship with The Mountain.’

“The mountain on which we played truant, and cut tour sticks in boyhood, spooned and picnicniced in our adolescence, and to which our later days are indebted for perennial streams of Cascade ale, our Christmas decorations, and no inconsiderable portion of our daily supply of milk.”

In every culture, anthropologists and sociologists find evidence that geological processes such as floods and earthquakes, together with large, impressive, or unusual geological relics—river canyons, mountains, beaches and even the shapes and colours of the stones lying around the place—inspire story-telling and artistic creations, influence cultural behaviours and customary practices, and lie embedded in every religious/legal ethical system. This con-fusion of the natural with the cultural is known as entanglement.

“When you go out there, you don’t get away from it all. You get back to it all. You come home to yourself. ”

In the Wellington Park Management Plan the mountain’s “earth systems”—its waterfalls, cliffs, gullies, rocks and viewpoints—are seen as simultaneously the “foundation for the Park's ecosystems and the basis for its high landscape value”. The values of the ecosystem (natural) and the landscape (cultural) are entangled.

Though some would go much further, it is generally agreed that landscapes are the result of the interaction between three forces: physical, biological, and cultural. (In some cases, this entanglement has become more widely appreciated shortly after the places were destroyed.) Academics consider that natural heritage cannot readily be disconnected from cultural heritage because “the framing and valorisation of every geological heritage site is conducted within its own contemporary cultural setting”. A particularly strong association or overlap between geological and cultural heritage values creates a geo-cultural heritage place.

‘It is likely that many Hobartians feel the Genius loci especially in the wilderness and wild places that make up Mount Wellington. For the nineteenth century traveller this may have been the walk to the summit, and the wonder at the panorama of the tiny town and its many bays and inlets spread out before them. For the twenty-first century traveller or recreation user, this is more subtle. Increasing built form and associated infrastructure of a major dimension diminishes this value. Genius loci in the case of Mount Wellington is intimately related to the maintenance of the wild and wilderness qualities of the mountain, to its geomorphology and landforms, its vegetation, its significant historical landscape values, and its lack of development.’ (Barnes)

“Landscape does not just shape language; the land itself is transformed by words, phrases and ways of telling’”

Ceremonial memento presentation during proceedings of the 1937 Opening of Pinnacle Road

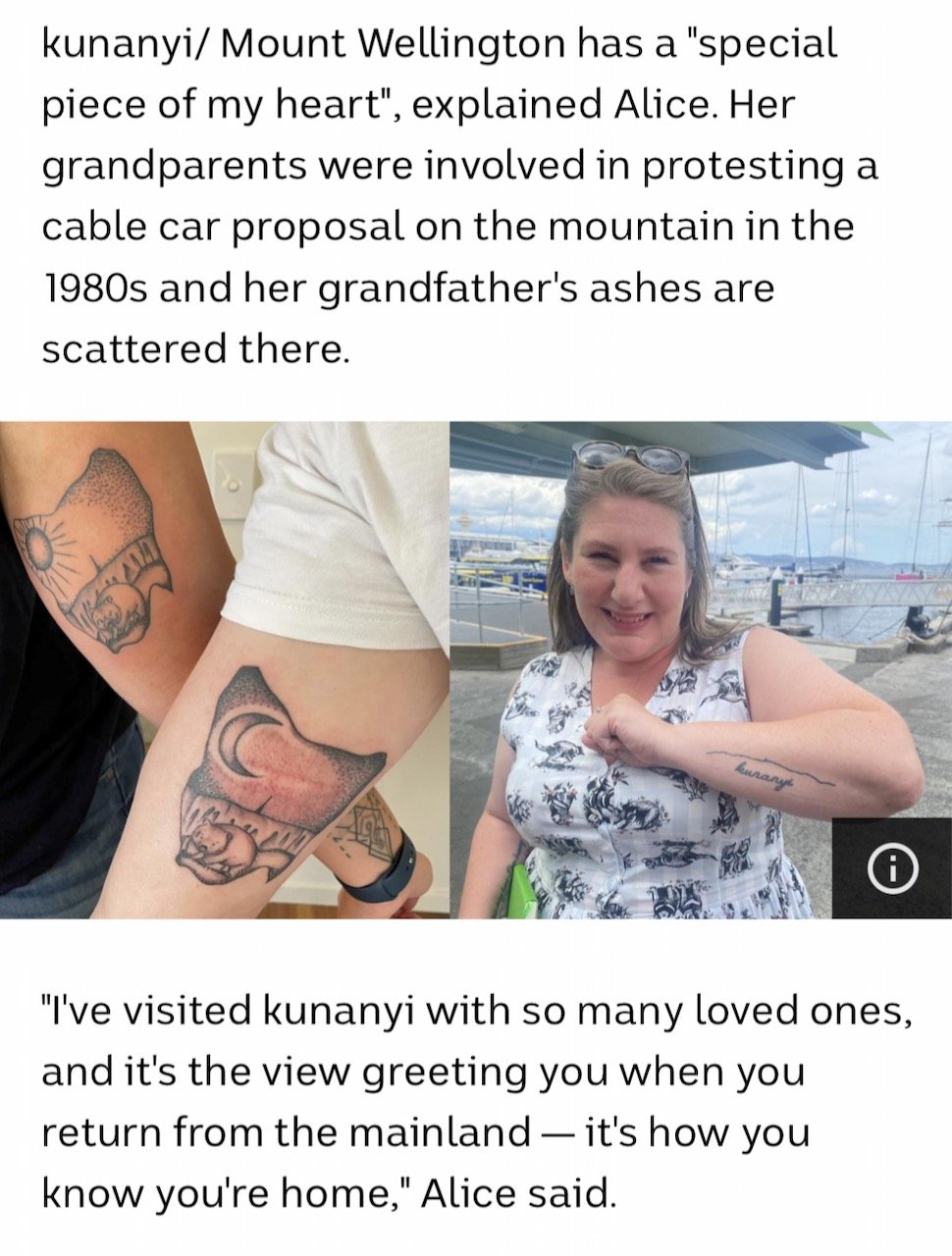

Into an astonishing questionnaire (see refs) hundreds of Hobartians poured out their hearts, telling the Wellington Park Management Trust of how they lost their virginity, proposed marriage, got married, took their kids and scattered their parent’s ashes up there on the mountain.

When asked “What value has the Mountain for you?” Hobartians revealed their journeys from experience to devotion. Their remarkable and unique love letters demonstrate Relph’s nexus of setting, activity and meaning, and show that attachment to the Mountain is widespread, long held and profound.

“The rolling, sweeping glory of the mountain is the first grand picture stamped on the mind of the Hobart born. ”

“Part of Hobart’s character comes from the Mountain Air.” wrote respondent #24 [No names, only numbers identify the participants]. Respondent 146 recalls, “While walking in the misty rain, my mind considered that I was able to take a walk in heaven.” Another remembered how (many, many years past) “When I was a small child, where I lived I had a great view of the mountain, and I thought that the snow-covered Springs Hotel was where Father Christmas lived.”“When dawn breaks and throws a caste of pink over the Wellington Wonderland–tell me a heart that is not moved.”

The Mountain’s value is as much as life itself. Some people value the Mountain to the extent that “it defines their lives”: “It’s the most important place in the world to me. I can’t imagine living anywhere else in the world.” (HC35)

“Go yourself [to an auction] and see what any historic painting of Mt. Wellington fetches. We all understand the value of this natural monument and the value that it has held for all those who have been here long before us.” (313)

“It is a part of Hobart’s soul.” (320)

“It is extraordinary the passionate love they have for the country of their birth, but I believe it is remarked that the Natives of a Mountain Land feel stronger attachment for their birth place than the Natives of the Plains.”

To some, the Mountain is alive, a living force that can teach us things great and small. It makes us what we are.

“She is an everyday weather advisor to me ... and I seek her advice on clothes for work each morning. Growing up in Glenorchy, the Mountain’s presence always guided me and watched over me.” (204)

“She has her own personality, a presence, sometimes cool, but always dignified, and we nestle just beautifully in her bosom.”

Without it, the people would be lost. Not simply because it is a landmark and a signpost of home, but because of its presence.

“I was born in Dynnyrne, so I have lived under the mountain all my life. The view from the summit is home. We lived in North Hobart for six months, in that time we could not see the Mountain at all; it was a very bad time, so many things went wrong, we had to move so we could once again see the Mountain. So you can see now why I love the Mountain, and if I cannot see it every morning I am lost.” (164)

It can be bitter-sweet. Respondent 269 wrote of her grief-stricken experience of the mountain as "the place where, after being kept on life support machines, after we took her home from the hospital, then to the mountain, my 9-day-old daughter took her last breath.”

* * *

From the Social Survey report’s very first sentence, Wellington Park is shown to be the community’s home away-from-home. Its natural, social capital. For many, that attachment is spiritual. The mountain-top is hallowed ground. Buried deep in the report was this revelation: The summit area is the place in the Park where the major number of ashes of deceased family members are scattered.

ABC news, July 2023

“The complex feelings of affinity and self assurance one feels with one’s native place rarely develop again in another landscape.”

The survey report author, Anne McConnell, argued that these social values have antecedents and thus, historical validity. They informed the original Mountain Park Act a century ago, and ‘appear’ to have applied since at least the early days of … Hobart.’ What is unstated, but strongly implied is that they likely applied for thousands of years before then too. Gwenda Sheridan made similar observations after a comprehensive study of creative responses to the mountain throughout time and space. So it appears reasonable for McConnell to have concluded that these values are the social values for the Park.

Coming full circle, Barnes concluded that ‘Much as a craftsman imparts something of his personality to the things he makes, so a community can transfer its character to a landscape.’

Sheridan’s report (Volume 2) links the concept to Tasmanian Aboriginal cultural life. ‘There is no reason not to believe that Tasmanian indigenous peoples held that Mount Wellington contained the association, the memory, the feeling, the concept of ‘Genius loci’.’ The Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre’s Heritage Officer, Sharnie Read, confirmed Sheridan’s reasoning. ‘For a lot of Aboriginal people, particularly down here in the south, kunanyi is such a dominant feature in our landscape. By landscape, I mean the view, the physical and human view as well as the presence of the mountain, including its sounds. Together, it is a Cultural Landscape to me as an Aboriginal person. There is a very strong connection, and the connection relies upon the view of kunanyi.’

“Aboriginal peoples’ connection and strength comes from the mountain itself. I love and value the beauty of kunanyi without necessarily walking there because there is a sense of connection and belonging for me and for my family group. It is part of a deeper spiritual connection I hold to the landscape of the mountain. When I go there as part of a community group, I go to the foothills, mostly into the water systems. When we leave, we walk away with a deeper sense of strength as individuals but also as a community. It’s not just strength of connection to a space, but strength that comes from identity, as Aboriginal people, together being connected to this island. This connection is based in a significant way on the view of the mountain. Whilst we are on that mountain, whilst we are physically connected to the mountain, we’re actually physically connected to our ancestors. Those stories lift us, but there is no other way to have that strength shared without physical connection. The best way to do that is to ensure that Aboriginal people have an uninterrupted access to our landscapes.”

The earliest sense of place for the Mountain is yet to be fully re-covered, but a clue hides within its placename kunanyi.

HERITAGE ASSESSMENT

Recognising the mountain’s Sense of Place is a heritage recommendation of Gwenda Sheridan. She argued that the Mountain’s genius loci be heritage listed: “The Genius loci for Mount Wellington needs to be recognised as an integral part of Wellington Park and its surrounds. This relates to the long-held perceptions, memories, meanings, and associations, and aesthetics of place. It must be retained. High priority.”

The Mountain’s Sense of Place is at the heart of the Wellington Park Management Plan. In the Plan, the Park has three overall value systems: Use Values, Natural Values and Cultural Values. Each is subdivided; and within the four fields of cultural value, the fourth is “sense of place” (Page 14 of the Plan). The plan recognises that the mountain is part of the community’s ‘extended sense of self’:

“The Park is more than a biophysical reserve, and more than the historical parts that make it up. It is, in fact, part of the community’s ‘extended sense of self’. That is, it is inextricably linked into the psyche and perhaps the being of the community of southern Tasmanians who live in its shadow.”

Sense of Place is identified in the Wellington Park Management Plan’s Statement of Significance.

Anne McConnell’s Pinnacle Development Plan states that ‘The social value of Wellington Park is underscored by...its overall contribution to the ‘sense of place’ of living in Tasmania.’

REFERENCES

Adam Barnes Mount Wellington and Sense of Place, UTAS thesis 1991

Gwenda Sheridan, The Historic Landscape Values of Mount Wellington, Hobart An evolution across time, place and space (WPMT 2010)